In Do We Need More Law Schools, I commented on the number of new law schools that have been in the works. In that post, I used the number of JDs granted per year, largely as a matter of convenience. But what about the demand for law school itself–the number of persons interested in going to law school. Several commenters suggested that the proper measure is the demand for lawyers, especially by firms that employ lawyers. While employment opportunities, and starting salaries, are a major factor affecting the demand for legal education, it is not the sole factor. Whatever the underlying causes, the demand for legal education says something about the need for more law schools (as opposed to more lawyers).

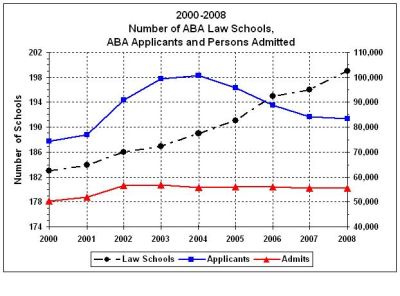

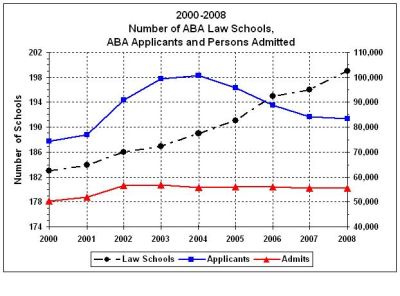

The above chart uses information drawn from the current (as of October 2, 2009) LSAC Volume Summary (under the “Data” section). For the Fall 2000 entering classes, 74,600 persons applied, of which 50,300 (67%) were admitted. For Fall 2008, 83,400 persons applied, of which 55,300 (67%) were admitted. From Fall 2000 through Fall 2004, the number of applicants increased to 100,600, of which 55,900 (56%) were admitted. From Fall 2004 through Fall 2008, the number of applicants fell by 17,200 persons (17%), but the number of persons admitted fell by 400 (less than one percent). During that same period, the number of law schools increased by 9%, from 183 to 199.

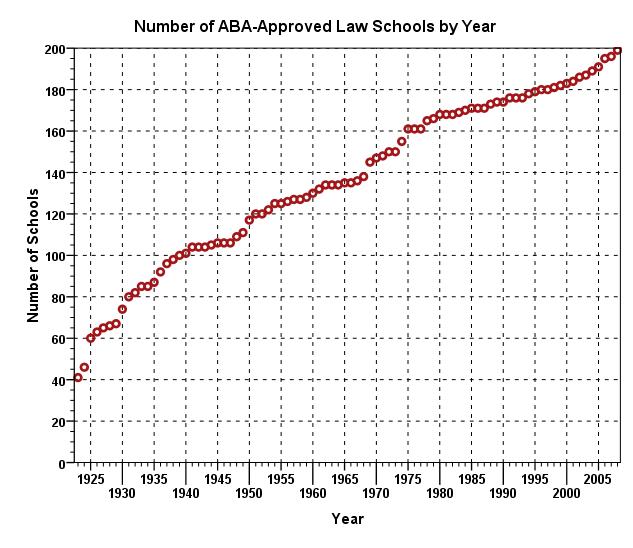

But compare that with the number of applicants for Fall 1991 through Fall 1995 (estimated by combining data from the applications per applicant chart in the LSAC report, National Applicant Trends–2008, with Table 1 in Charles Longley, Law School Admissions, 1985 to 1995, Assessing the Effect of Application Volume (1998) (LSAC Research Report Series, No. RR-97-02)). The estimated number of ABA applicants to fell from a high of 86,700 for Fall 1992 (176 schools) to 72,800 for Fall 1995 (179 schools). Thus, since 1992, the number of applicants has fallen, risen, and fallen again, for a net loss of 3,300 persons (almost 4%), while the number of ABA law schools has increased by 22 schools (over 12%).

Because Longley focused on ABA applications and admissions, rather than persons admitted, I do no not have the numbers of the number of persons admitted. As shown in the ABA’s table, Enrollment, and Degrees Awarded, first-year enrollments have seen some dips since Fall 1991 (44,050), but have increased to 49,414 in Fall 2008 (an increase of 12%). That tracks the JDs awarded by ABA law schools (see the chart in Do We Need More Law Schools?).

So we have more law schools chasing the same number of applicants, but enrolling more students. I don’t think the increased competition has hurt the elite law schools. That means that the rest the law schools, particular those in U.S. News Tier 4, have more competition for students, and will have to dip deeper into the applicant pool. For a law school, lower academic credentials tend to translate into lower Bar passage rates, especially in high cut-score states, such as California.

So, if you concluded from my earlier post that, as a professor at a Tier 4 school, I must be in favor of more law schools, you were wrong. Apparently, the numbers do not speak for themselves, so let me be clear:

Flat Demand + More Law Schools = Trouble

That said, since Fall 2003, law schools have held the number of admitted applicants relatively flat, and even cut the numbers somewhat. Yet enrollments have still gone up. That’s because more of the admitted applicants are choosing to go to law school. For Fall 2003, 48,900 out of 56,800 admitted persons (86%) actually enrolled, while, for Fall 2008, 49,414 out of 55,500 (89%) enrolled (LSAC Volume Summary).

Gary Rosin

Law-School Debt Loads

Monday, January 18th, 2010In her article, “Linking Debt and Income,” Inside Higher Ed, January 18, 2010, Jennifer Epstein reports that the U.S. Department of Education recently proposed that vocational and for-profit colleges meet minimum standards for debt-to-income ratios for recent graduates. The average debt repayment could be no more than eight percent (8%) of expected earnings in the field. The presumptive expected earnings would be the 25th percentile of incomes in the field for which they had been trained.

How would that work for law schools? Going to law school is expensive, and often financed with debt. The 2009 Survey Results of the Law School Survey of Student Engagement tells us that 29% of the students surveyed expected to graduate with law-school related debt of at least $120,000. The following chart from page 14 of the 2009 Annual Survey of law students shows the law-school debt levels expected by current law students.

According to the May 2008 Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (National Cross-Industry Estimates [.zip file]) the 25th percentile of annual income for lawyers was just under $75,000. That would make the maximum annual payment just under $6,000. Assuming a modest ten percent (10%) interest rate,* the maximum average school debt would be just over $45,000.

But over two-thirds of students surveyed in 2009 by LSSSE expect to graduate with law school debt of $60,000 or higher. According to Epstein, schools that don’t meet the eight percent (8%) of presumptive earnings could show

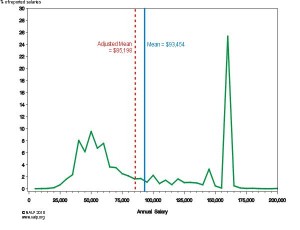

The following chart from the National Association of Law Placement shows the distribution of salaries of the Class of 2008:

Class of 2008, Distribution of Salaries (NALP)

The overall median of $72,000 is just under the May 2008 25th percentile of lawyer salaries ($75,000), so there is no wiggle room there.

Should law schools start reporting salary and debt-load information for its recent graduates?

posted by Gary Rosin

*Interest rates on guaranteed student loans in repayment are now about 2.5%. I’ll have to check on the current average for non-guarnateed loans. In event, current interest rates are abnormally low.

Posted in Commentary, Law Schools | No Comments »