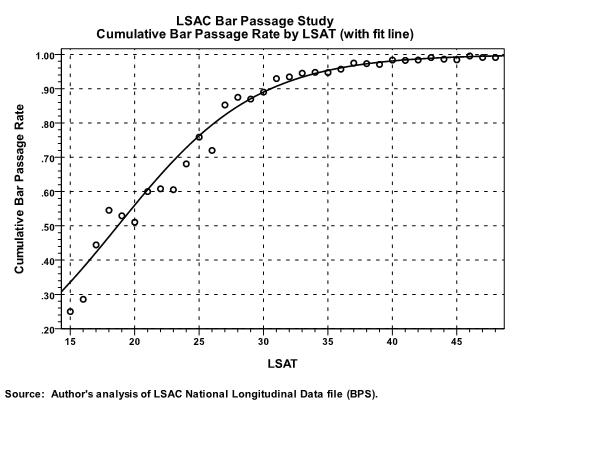

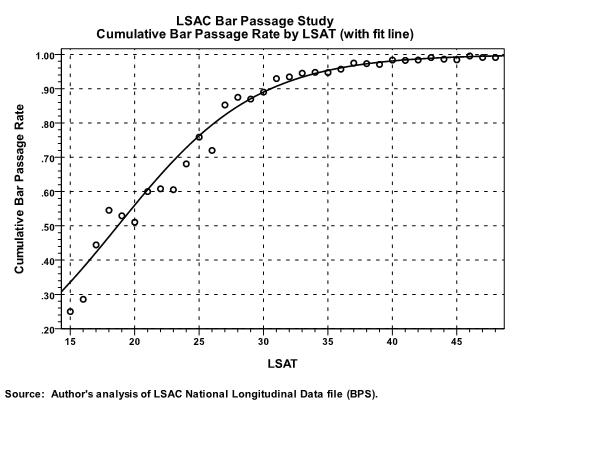

In recent years, there has been great concern about law schools relying too heavily on LSAT scores in admissions. The argument is that LSAT scores are at best an imperfect predictor of the academic success of individual law students, as measured by first-year GPAs. Moreover, academic success, is an even more imperfect predictor of success as a practicing lawyer. That said, the LSAT is more reliable when it comes to the predicting the success of groups, including Bar passage rates. For example, consider Chart 1, based on the data used in the LSAC Bar Passage Study, which shows the cumulative Bar passage rates over multiple attempts of persons with the same LSAT score:

Chart 1

Note: at the time of the LSAC Bar Passage Study (the entering class of Fall 1991), LSAT scores were reported on a scale that ranged from 10 to 48, rather than the current 120-180 scale.

Perhaps the most notable feature of the curve shown in Chart 1 is that a one-unit difference in LSAT (e.g., 35 vs. 36) has a larger effect on cumulative Bar passage as LSAT drops—the curve is much steeper at an LSAT of 19 that it is at an LSAT of 40. This phenomenon is important in crafting an entering class, which will include persons with a range of different LSATs. The ramifications of the phenomenon loom especially large for law schools with lower LSAT medians and 25th and 75th percentiles.

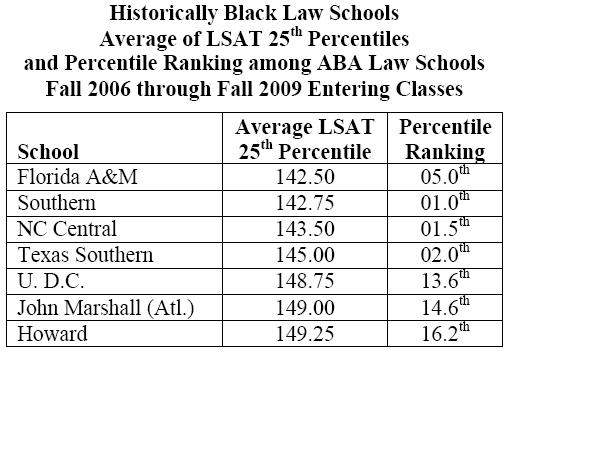

And there’s the rub: many of the historically Black law schools have entering-student LSAT scores at or near the bottom of those of all mainland law schools (i.e., excluding Puerto Rica and Hawaii). For example, over the Fall 2006 through Fall 2009 entering classes, the average of the LSAT 25th percentile for each school averaged 154.7, with a standard deviation of 5.68. The bottom four ABA law schools were Florida A&M, Southern, North Carolina Central and Texas Southern, while District of Columbia, Atlanta’s John Marshall and Howard were grouped around the 15th percentile.

While each school is required to report recent cumulative Bar passage rates to the ABA, that information is neither published in the ABA-LSAC Official Guide to ABA-Approved Law Schools (as of the 2011 edition), nor distributed to all ABA law schools via the annual “ABA take-offs.” As a result, there is no data from which to perform a study along the line of that reported in my article, Unpacking the Bar: Of Cut Scores and Competence, 32 J. Legal Prof. 67 (2008) (SSRN Absttract No. 988429), for first-time Bar passage rates. While the shape of the resulting logistic “S” curve is unknown, the effect of a one-point change in law-school LSAT on law-school cumulative Bar passage rates will be much larger at the low end of law-school LSATs than it is at the high end, which means that the historically Black law schools will be at much greater risk of being affected by raising the minimum “ultimate” (cumulative) standard in 301–6 from 75% to 80%.

Posted by Gary Rosin

This entry was posted on Friday, March 25th, 2011 at 5:21 pm and is filed under ABA, Admission, Bar Exam, Commentary, Empirical Studies, Law Schools, LSAT. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

The LSAT and Historically Black Law Schools

In recent years, there has been great concern about law schools relying too heavily on LSAT scores in admissions. The argument is that LSAT scores are at best an imperfect predictor of the academic success of individual law students, as measured by first-year GPAs. Moreover, academic success, is an even more imperfect predictor of success as a practicing lawyer. That said, the LSAT is more reliable when it comes to the predicting the success of groups, including Bar passage rates. For example, consider Chart 1, based on the data used in the LSAC Bar Passage Study, which shows the cumulative Bar passage rates over multiple attempts of persons with the same LSAT score:

Chart 1

Note: at the time of the LSAC Bar Passage Study (the entering class of Fall 1991), LSAT scores were reported on a scale that ranged from 10 to 48, rather than the current 120-180 scale.

Perhaps the most notable feature of the curve shown in Chart 1 is that a one-unit difference in LSAT (e.g., 35 vs. 36) has a larger effect on cumulative Bar passage as LSAT drops—the curve is much steeper at an LSAT of 19 that it is at an LSAT of 40. This phenomenon is important in crafting an entering class, which will include persons with a range of different LSATs. The ramifications of the phenomenon loom especially large for law schools with lower LSAT medians and 25th and 75th percentiles.

And there’s the rub: many of the historically Black law schools have entering-student LSAT scores at or near the bottom of those of all mainland law schools (i.e., excluding Puerto Rica and Hawaii). For example, over the Fall 2006 through Fall 2009 entering classes, the average of the LSAT 25th percentile for each school averaged 154.7, with a standard deviation of 5.68. The bottom four ABA law schools were Florida A&M, Southern, North Carolina Central and Texas Southern, while District of Columbia, Atlanta’s John Marshall and Howard were grouped around the 15th percentile.

While each school is required to report recent cumulative Bar passage rates to the ABA, that information is neither published in the ABA-LSAC Official Guide to ABA-Approved Law Schools (as of the 2011 edition), nor distributed to all ABA law schools via the annual “ABA take-offs.” As a result, there is no data from which to perform a study along the line of that reported in my article, Unpacking the Bar: Of Cut Scores and Competence, 32 J. Legal Prof. 67 (2008) (SSRN Absttract No. 988429), for first-time Bar passage rates. While the shape of the resulting logistic “S” curve is unknown, the effect of a one-point change in law-school LSAT on law-school cumulative Bar passage rates will be much larger at the low end of law-school LSATs than it is at the high end, which means that the historically Black law schools will be at much greater risk of being affected by raising the minimum “ultimate” (cumulative) standard in 301–6 from 75% to 80%.

Posted by Gary Rosin

This entry was posted on Friday, March 25th, 2011 at 5:21 pm and is filed under ABA, Admission, Bar Exam, Commentary, Empirical Studies, Law Schools, LSAT. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.