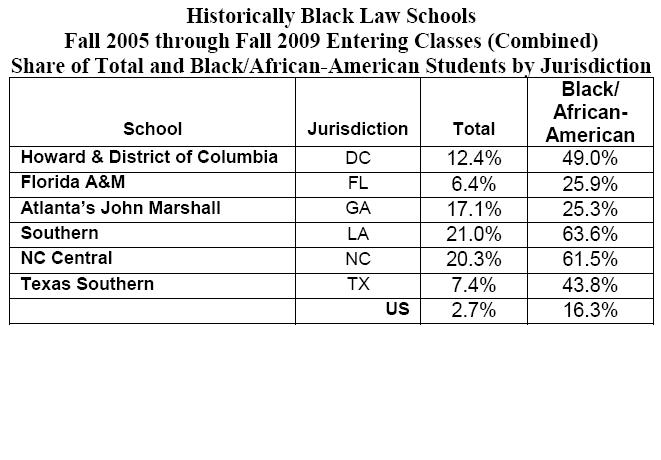

Florida A&M, Howard University, North Carolina Central, Southern, and Texas Southern were all formed, as early as 1869 (Howard), but largely in the 1940’s, with the primary mission of educating Black/African American lawyers. With those roots, one might expect that their student bodies would still be predominately Black/African American. But, as Bob Dylan once sang, “the times they are a changin’.”

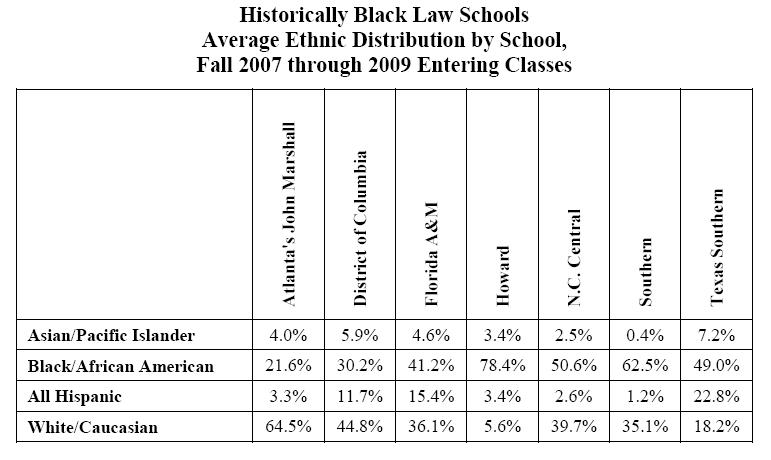

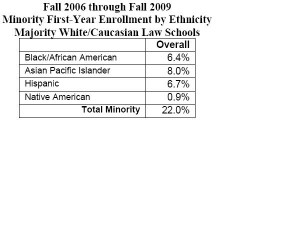

As shown in the above table, over the three most recent academic years for which information has been published in the Official Guide, at Atlanta’s John Marshall, White/Caucasian students predominate, with Black/African-American students just over a fifth of the class. At the University of the District of Columbia, White/Caucasian students have constituted a plurality of the entering classes. During that period, at three of the remaining schools, Florida A&M, North Carolina Central, and Texas Southern, Black/African-American students constituted at least a plurality of entering students, with the last two hovering near 50% of the class. Only Howard and Southern remain strongly Black/African American institutions. During that period, at five of the schools, White/Caucasian students have a substantial presence—at least 35%. At Texas Southern, the second-largest component of entering classes has been Hispanic students. Only at Howard is predominantly Black/African-American, with no strong presence of any of the other ethnic groups.

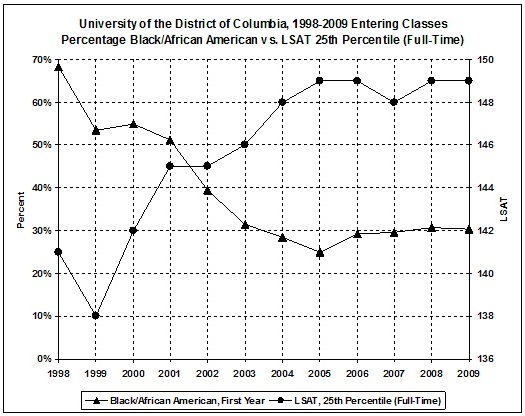

As recently as 1998, Black/African-American students made up 68.3% of the entering class at the University of the District of Columbia (DC). Beginning with the next entering class, the Black/African-American share of the class began falling, and reached a low of 25.0% for the 2005 class. What happened after 1998? According to the Official Guide, DC was accredited in 1991, so it would have been due for a sabbatical inspection around 1998.

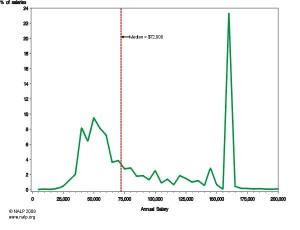

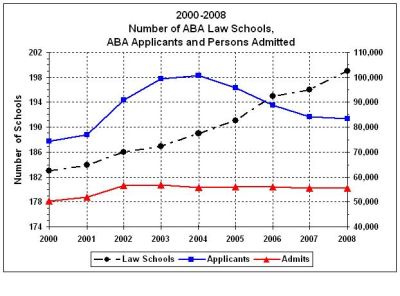

Professor John Nussbaumer argues that the ABA uses its initial and periodic accreditation reviews to pressure law schools to raise the LSAT scores of the low end of their entering classes. John Nussbaumer, The Disturbing Correlation between ABA Accreditation Review and Declining African-American Law School Enrollment, 80 ST. JOHN’S L. REV. 991 (2006) (“Disturbing Correlation”); John Nussbaumer, Misuse of the Law School Admissions Test, Racial Discrimination, and the De Facto Quota System for Restricting African-American Access to the Legal Profession, 80 ST. JOHN’S L. REV. 167, 178-79 (2006) (“Restricting Access”). As shown in the following chart, decreases in the Black/African-American share of entering classes are largely mirrored by increases in the 25th percentile of the LSAT scores of the entering classes:

Although the ABA began including in the Official Guide data on entering classes of Atlanta’s John Marshall as of its Fall 2007 class, it is likely that John Marshall is the “School X” described in “Case Study One” discussed by Professor Nussbaumer in Disturbing Trend, 80 ST. JOHN’S L. REV. at 178. First, it “is located in a major metropolitan area with a large minority and African-American population.” Second, it “seeks to provide non¬traditional students with access to the legal profession.” Third, Prof. Nussbaumer says that School X was “recently” given full ABA approval. Disturbing Trends was published in 2006, in the first issue of volume 80; Atlanta’s John Marshall was fully accredited in 2005.

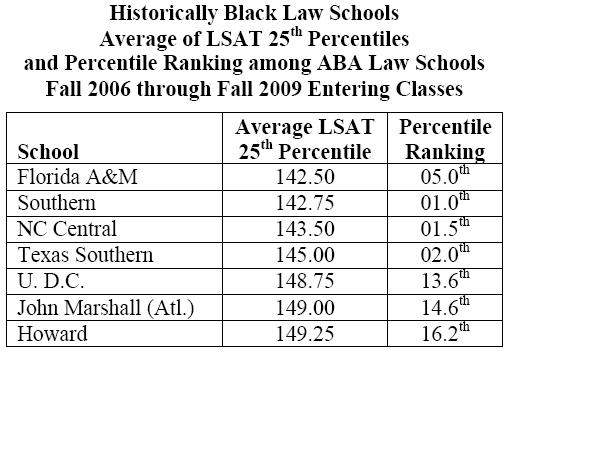

In any event, School X also underwent a radical demographic transformation. Between 1999 and 2004, it raised the LSAT 25th percentile of entering classes from 138 to 148. Concurrently with that increase, total minority enrollment fell from 74% to 46% (i.e., it became a majority White/Caucasian school), and Black/African-American enrollment fell from 62% to 32%. Id. at 178 & 181-F, tbl. 9.

By the time the law school at Florida A&M was reorganized after a hiatus of over thirty years, and the ABA began publishing information on its entering classes, it was already only a plurality Black/African-American institution.

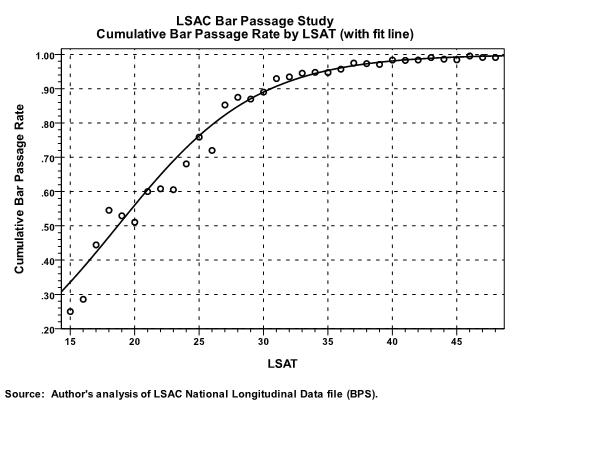

The ABA may not have a so-called “floor” on the LSAT scores of admitted applicants. We do know that the ABA has used Bar passage rates to measure not only compliance with Standard 301 (adequacy of program of legal education), but also Standard 501(b):

A law school shall not admit applicants who do not appear capable of satisfactorily completing its educational program and being admitted to the bar.

2010-2011 Standards and Rules of Procedure for Approval of Law Schools, Standard 501(b) (emphasis added). Even before the adoption of Interpretation 301–6, the ABA’s Accreditation Committee had been using a standard for first-time Bar passage of below 70% and more than 10 points below the state average for ABA-accredited schools Bar passage standards no being proposed are the standards that the ABA had been using. See, e.g., Memorandum from Greg Murphy, Chair, Accreditation Committee, to Richard Morgan, Chair, Standards Review Committee, on Interpretation 301–6,at 1 (May 2, 2007) (“Murphy Memorandum”)(copy on file with author).

The Murphy Memorandum also indicates that the Accreditation Committee also was relying on cumulative (ultimate) Bar passage rates, but does not indicate the minimum used by that committee. However, when the Standards Review Committee first proposed the use of difference scores and cumulative Bar passage rates, it proposed a 10% difference score and an 80% cumulative Bar passage rates. Memorandum from Richard L. Morgan, Chair and Hulett H. Askew, Consultant, to Standards Review Committee, regarding Wednesday, May 17, 2007 Hearing and Meeting (May 16, 2007). Given that the 10% difference score was the standard being used by the Accreditation Committee, it suggests that the 80% cumulative rate may also have been the standard that that committee was then using.

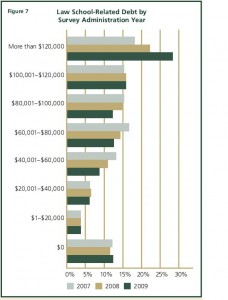

Given the links between both first-time and cumulative Bar passage rates and group LSAT scores, quickly increasing a law school’s Bar passage rates means quickly increasing the LSAT scores of its entering classes. The widespread increases in the LSAT 25th percentiles at historically Black law schools, and the associated decreases in the share of Black/African-enrollment, are probably associated with the use of the very Bar passage standards which are again being proposed.

Posted by Gary Rosin

Changing Demographics of Historically Black Law Schools

Sunday, March 27th, 2011Posted in ABA, Admission, Bar Exam, Commentary, Diversity, Empirical Studies, Law Schools, LSAT | No Comments »